Sherlock Holmes: Nemesis Review

Frogwares Game Development Studio has continued their highly successful series of adventure/mystery games based on the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, created by Arthur Conan Doyle. Beginning with The Mystery of the Mummy, and continuing with The Case of the Silver Earring and Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened, the newest offering -- Sherlock Holmes: Nemesis -- pits the renowned consulting detective against the great mastermind and gentleman-burglar Arsene Lupin -- a character created by French author Maurice LeBlanc. (Sherlock Holmes appeared in several novels by LeBlanc, always as the arch-nemesis of Lupin.)

As the game begins, Holmes receives a note from Lupin, informing Holmes that he (Lupin) will be pitting the honor of France against that of England, as he prepares to steal five great treasures of Britain. Without naming the five specific targets, he proceeds to lead Holmes on a merry chase across the landscape of London, always staying just one step ahead of Holmes and the ever-present Watson.

Through the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square, to the Tower of London, and the British Museum, nothing is sacred and no place too daring for the bold Frenchman -- not even Buckingham Palace itself. It is up to the player to decipher the constant riddles left by Lupin as clues to his next movements, track him down, and save the treasures -- and preserve the honor of England.

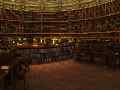

The Sherlock Holmes series of adventure games from Frogwares is well-known for several common features: excellent, highly-detailed graphics; good 3D rendering of the characters; high-quality music; and a good mixture of inventory and logic puzzles. In Nemesis, the tradition not only continues, but is improved upon. As indicated by the screen shots in the sidebar, the scenes in the game are wonderfully crafted, down to the minutest detail. The sense of realism and completeness in each of the many locations speaks eloquently for the caliber of the game's artists.

The game has quite a large footprint, spanning as it does not only the city of London in general, but specific sites, as mentioned above. While places such as the National Gallery and the British Museum have been "slimmed down," in terms of their true blueprint, there are still enough rooms, hallways, cellars, cul-de-sacs, etc. to explore, to keep an adventure gamer satisfied. And in each case, the artwork is rich and colorful, and provides enjoyable "eye candy" (including frequent in-scene animations, such as burning torches, rain falling, characters fidgeting, and so on).

As with previous games, Nemesis provides all of the features that I look for in a well-designed adventure game. The inventory is easy to use; the menu system is intuitive; there is no limit to the number of games that can be saved; and additional options include the ability to review all dialogues that have taken place thus far in the game, a map that can be used to move quickly between known locations, an archive of all documents encountered during the game, and even a sort of "journal" that periodically summarizes what has taken place so far. (This journal is also occasionally a good source of hints for "What do I do now?")

In addition, video cut-scenes throughout the game are rendered exceptionally well, supporting the superior quality of the rest of the artwork. The only thing missing, in my opinion, was the ability to replay any of the video scenes for later reference.

A common theme throughout the game is the riddles presented by Lupin. They typically take the form of notes left behind, as he slips away from his most recent burglary only moments before Holmes appears. It soon becomes apparent that, to Lupin, it is all more of a game than anything else. How long can he provide clues for Holmes to follow, before being apprehended himself? The riddles are sometimes straightforward, sometimes infuriatingly obscure. But it is always necessary to solve each riddle before you can proceed to the next phase of the game. At times, the game itself presents "checkpoints" in the form of questions to the player. The story will be interrupted, and a question will appear on the screen, which the user must answer before continuing.

This latter feature reinforces that Nemesis -- like so many other adventure/mysteries -- is a highly linear game. By nature, combining a mystery (which involves step-by-step exploring and information gathering) with a complex story line (which must develop in a pre-determined manner) often results in this kind of linearity. The strength of such a design is that it allows for more complex plot development, and more controlled game play; the weakness is that there are often points in the game where no further progress can be made until one (and only the right one) particular action is taken. And if that action is unclear (or the answer to a specific question is unknown), there may be little more to do until that hurdle has been overcome.

Nemesis does suffer from a design flaw often seen in games of this linearity. That is, a particular object, or a certain "hot spot," or some specific action may not be available until some other "trigger" has taken place in the game. For example, there may be a hammer lying on a table. Upon first encountering it, the hammer is not active; it can not be picked up, or interacted with in any way. However, later -- after discovering that a hammer would be useful at some particular moment -- the hammer can suddenly be picked up and used. This challenges the realism of the game, as it would be far more intuitive (and realistic) to be able to pick up the hammer at any point during the game, even if it cannot be used until much later.

Unfortunately, this characteristic of the game, combined with the aforementioned game linearity and large footprint, often resulted in a tedium caused by the necessity to continually re-visit locations, simply to check what new active spots, or dialogues, or usable objects, might have appeared since the last visit to that location. One saving grace is that many times Holmes could not leave the immediate scene if there were still tasks to accomplish there -- thereby saving extensive unnecessary traveling. This did not, however, eliminate the need to constantly talk to the same people, or re-check things that had already been checked, in case something had changed.

The puzzles in the game are of three general types: there are, as already mentioned, the riddles that arise throughout the game, and which need to be solved to proceed; there are numerous inventory puzzles, where some object needs to be found to interact with some other object, to obtain a specific result (e.g., finding a key to open a locked door); and there are a handful of logic puzzles, most of which appear as full-screen puzzles when activated, providing the gamer with a focused (non-timed) brain teaser to solve. In the latter case, clues to solving the puzzle may take several forms: notes left by Lupin, documents found during game exploration, conversations with other characters, or simple intuition. I found the combination of these three different puzzle types to provide an excellent balance, with a challenge level that ranged from fairly easy to moderately difficult.

One other minor flaw in the game design could be referred to as the "magical hinges" syndrome. Approaching a building or room, and clicking on the door handle, would invariably cause the door to open away from the player. Once inside that door, however, turning around and clicking on the handle again would, once more, cause the door to open away from the player -- as though the hinges had been reversed. Far from being a distraction, however, it provided a bit of levity each time I saw it happen.

Although most areas are easy to navigate, and objects are easy to see and/or retrieve, there are occasional spots where extensive "pixel hunting" is necessary -- either because an item is so small, or because the artwork is cleverly hiding it. While searching a scene is a standard part of any adventure game, more than once I was a bit annoyed by how tiny, or how remote, a certain object was -- requiring an inordinate amount of screen-searching.

I mentioned the music in passing, and I must return to that topic, as it warrants comment. I'm sure that different gamers' responses to the music will be quite different; mine was that it was a superb addition to an artistic game. Keeping with the theme of the story, and the time in which it takes place, the background music (which was continual throughout the game, not just occasional) was classical music, typically violin and/or piano, along with various other instruments. Much of it was identifiable classical music -- Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, etc. However, some was also unique to the game. As I am a classical musician, I appreciated it tremendously -- at times, even pausing just to listen. At the same time, I can imagine that gamers for whom classical music is not their genre-of-choice might have a different response. In any case, I feel that it was implemented well, integrated with the action going on at the time, and supported the game as a whole.

A word about the hardware requirements (see sidebar for details): With each new game that Frogwares has developed, the craftsmanship has increased noticeably. The ability to control textures, shading, shadows, anti-aliasing, anisotropic filtering, and so on is remarkable. At the same time, there is a cost for such things. As a result, several of the recent offerings from Frogwares (including Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened, Dracula: Origin, and now Sherlock Holmes: Nemesis) require the Ageia PhysX graphics accelerator. For systems that do not have a PhysX hardware accelerator, a software emulator is installed along with the game.

I played The Awakened on a system without the hardware accelerator (using the software emulator); and I played Nemesis on a system with the PhysX hardware accelerator (and a dual-processor video card). I noticed a marked difference between the two. On The Awakened, I needed to turn off most high-end graphics capabilities, and play at a much-reduced quality level. With Nemesis, I set all graphics and sound parameters as high as they would go, and never had a single problem with the game. As a result, I recommend having not just the minimum requirements, but a stretch beyond -- particularly for things such as CPU speed, memory, video processor, etc. I believe it will make for a more satisfactory gaming experience.

The game is rated "E" (Everyone). As is the case with the original Sherlock Holmes stories, the game is quite mild, despite the focus on the burglaries. Sherlock Holmes mysteries have traditionally transcended all ages. And in Nemesis, the puzzles and the story line are well within the grasp of children. There is sufficient game play to provide many hours of entertainment, making this a game that I highly recommend for anyone who appreciates high-quality adventure/mystery games.

-- Frank D. Nicodem, Jr.